Why So Many Working Class Americans Feel Left Out

The social advantages of higher education have never been greater

This week I’m excited to publish a coauthored article written with Sam Pressler, author of Connective Tissue. Sam was a collaborator on our recent survey report, Disconnected: The Growing Class Divide in American Civic Life. Sam is doing incredible work, and if you don’t already subscribe to his newsletter I’d highly recommend it!

Earlier this week, Donald Trump became president for the second time. Although Trump won more convincingly this time around, he won in much the same way. In 2024, Trump received robust support from Americans with a high school education or less (59 percent), including nearly seven in ten white Americans without a degree.

Trump’s continuing success with working-class voters has been a perennial topic of discussion since he first entered politics. Matt Grossman’s and David Hopkin’s excellent book, Polarized by Degrees, offers critical insight on this phenomenon. Other explanations are a bit less nuanced, attributing Trump’s support among those without degrees to racism or sexism.

One critical reason why the political trajectory of Americans without college degrees has been mystifying to so many is how little attention has been paid to their diminishing social and civic opportunities.

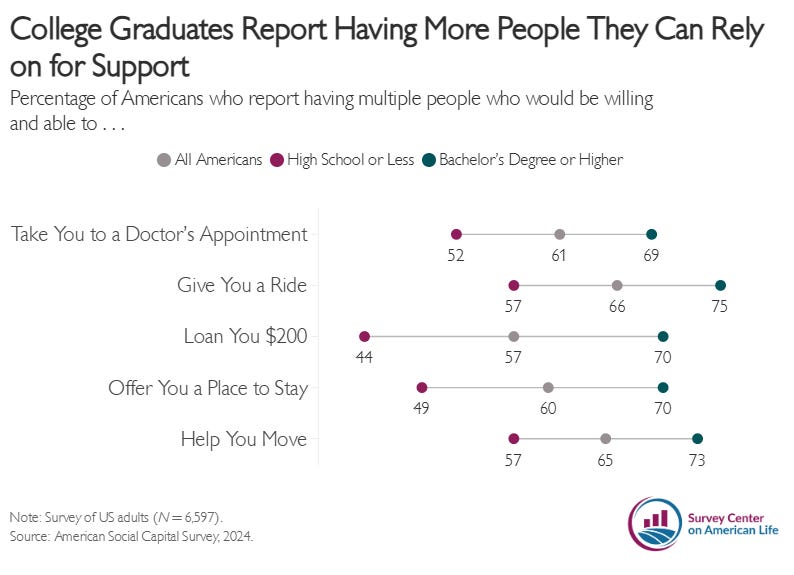

A college degree is not simply a door to increased economic opportunities or a more stable financial future; it’s a path to a more connected social life. College graduate have robust civic attachments, large friendship circles, and deep social networks. They feel better about the direction of the country, the functioning of our political and economic system, and their own future. Americans without degrees, in contrast, have increasingly been left out and left behind.

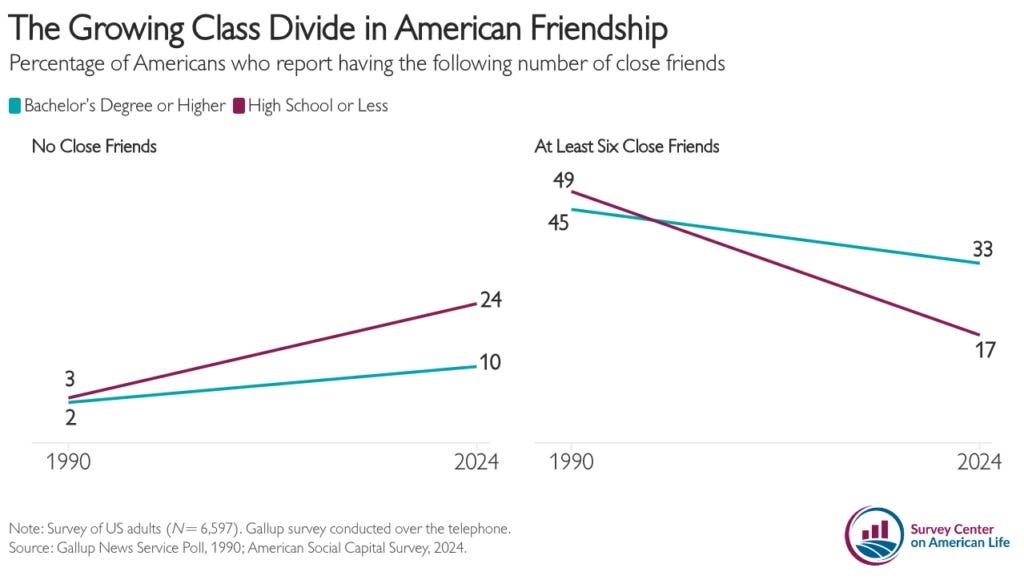

In a recent report, “Disconnected: The Growing Class Divide in American Civic Life,” we found that nearly a quarter of Americans without degrees report having no close friends, compared to 10 percent of Americans who completed college. It’s worth holding on this point for a second: the magnitude is jaw-dropping, but the meaning behind it is tragic. That’s no friends to pick them up when they’ve fallen on hard times, no friends with whom to share stories and heartfelt conversations, and no friends to accompany them through the inevitable ups and downs of life. A modest wage increase does little to reassure Americans feeling lonely and disconnected that everything is working as it should.

It wasn’t always this way. In 1990, nearly all Americans, regardless of their educational attainment, reported having a robust number of close friends. In the decade Robert Putnam wrote Bowling Alone, only three percent of Americans without degrees and two percent of Americans with degrees reported having no close friends. But since then, something fundamental has shifted in the fabric of American life, transforming the process of developing rich social connections from a broadly shared experience to a privilege reserved for an educated minority.

Why have Americans without degrees struggled so much more to maintain these critical social connections?

The class-based divide in friendship is a reflection of America’s civic stratification. Noncollege Americans are dropping out of civic life at far higher rates than college graduates. College graduates and those without degrees once had similar rates of religious membership, but now it’s college graduates who are significantly more engaged in regular religious practice. The decline of private-sector unions has also undercut the social support system of workers who do not have college degrees. The rise of gig work, irregular schedules, and less steady employment — which are overwhelmingly experienced by Americans without college degrees — also reduce opportunities to cultivate connection, both inside and outside of the workplace. Recent research has shown that the workplace serves as a critical source of social capital, but much more so for college graduates.

As socializing has become more expensive, the greater financial resources of college graduates confer meaningful social advantages. College graduates tend to have more stable jobs and more disposable income, which matter more as commercial spaces and activities occupy a growing share of America’s civic infrastructure. Whether getting a drink or dinner with friends, joining a gym or exercise group, or participating in an art class, everything is a lot more difficult if you’re strapped for cash. Access matters, too. College graduates tend to live in neighborhoods served by a wider array of commercial and public amenities. Even if those without degrees wanted to take advantage of these civic opportunities, they tend to have much less access in their communities.

But perhaps one of the biggest benefits of a college education is the structure and support that seem to naturally come with it. Most personal relationships develop slowly over time; repeated interactions are required to establish long-term trust and belonging. A 9-to-5 job, marriage, religious and community membership, and homeownership are experiences that provide structure to our lives. They offer established, consistent, and ongoing outlets for us to build relationships, and the relationships we form through these structures provide us with the information and encouragement to get even more involved. It is these overlapping webs of associations, relations, and commitments that engender so much of the meaning and belonging that make our lives worth living.

Americans who are unmarried, have irregular employment, are not attached to a church or place of worship, and rent rather than own are just as capable of forging close social connections. But it requires significantly more personal effort. Without institutional support, Americans are forced to do all the work themselves, from identifying opportunities to managing the scheduling and planning to, perhaps the hardest part, showing up alone. Social connections created outside of a shared institution — such as work, school, or church — require greater resources to build and more intentionality to maintain. Belonging and trust are more slowly earned, more tenuously held, and more easily broken.

But to only focus on these systemic issues is to miss the deeply personal and tangible hardships that come with being on your own, which we heard about in interview upon interview. Up close, the pain is heartbreaking:

“Once I get an income and a vehicle, I’m gonna go volunteer somewhere—just to do something for other people, you know. Just wanna volunteer ’cause I like to, but I can’t because of limited funds and transportation … I'm in this physical pain every day [and] the nearest bus stop to me is 2 miles.” - Paul, 47-year-old high school grad

“Everybody has some type of alternative motive or they're good to you until they got you and then they get you. And it's like ‘Oh OK, you are showing your true colors.’ I have had a couple of friendships that I tried to establish over the course of the past year that didn't quite pan out the way that I had wanted … You just get up and keep on moving.” - Luke, 39-year-old high school grad

“Relationships and friendships come and go … most of the people who [were] coming to movie nights and stuff back in the day when I did them were only showing up for the free food … I also used to go to concerts with a lot of people. It turned out that I’d be buying the dinner, and then once my money went away, so did the people. So I suffered a lot of friendships back then because of that.” - Brandon, 38-year-old high school grad

A college degree has long been viewed as a critical way of securing economic opportunity and financial stability. But this research suggests the benefits of having a degree — and the consequences of not having one — extend far beyond these important economic outcomes to our experiences of community, friendship, and social support.

When it comes to the way people live, and, increasingly, how they vote, the education divide has never been more important.

Excellent piece, thank you.

Putnam determined that the greater the inequality the less connected people feel. The decline in friendships in the US tracks with ever increasing inequality. The federal minimum wage is still $7.90 / hr. It has not increased since 2009. And the last legislation that was passed to increase it was 2007. States now compete with one another and developing countries to provide the lowest wage workers.

The minimum wage in Australia is $24.10 / hr which is still low, but not as crushing as $7.90 in the US or even $15/hr which many states have increased to.

People do not have time to connect bc they are struggling to survive. Congress meanwhile conducts studies on price gouging rather than deal with the underlying problem of low wages.

The pandemic brought a sudden increase in wages as well as supply chain disruptions. The US could have weathered the latter better if wages hadn’t been so far behind livable.

Allowing housing to become a speculative asset is also not helping matters. Allowing private equity to get into energy efficiency is also having detrimental effects as they scape the subsidies off the top and leave homeowners with the cost.

Interest rates on student loans have been absurd for decades and Congress failed to address it until.

Congress could literally pick any one of these problems to solve and it would have an outsized impact on people’s lives.